It’s long been known that bad investment decisions can be caused by our susceptibility to emotions and cognitive errors. But to really understand these behavioural risks and how to avoid them, it helps to see how they work in different ways. The analyst James Montier once used some research about goalkeepers to do just this, and this is how he put it...

Imagine you’re a goalkeeper facing a penalty kick. As the striker hits the ball, is it best to dive left, right or stay in the centre? In research, goalkeepers have been found to dive one way or the other a massive 94 percent of the time. Yet the optimal strategy is to remain unmoved in the middle of the goal.

So why do goalkeepers tend to dive one way or the other? The answer is that faced with a likelihood of conceding a goal, their instinct is to be seen to be doing something to stop it. If the ball flies into the top left or right corner, they’d surely be berated for remaining unmoved. But if they dive the wrong way… well, at least their intentions were good.

This is called action bias, and it manifests itself in different ways. It could be changing queues at a supermarket checkout, taking an alternative route on a congested road or trading shares absent-mindedly. This instinctive desire to take action gives us a sense of control, yet the outcome is likely to be the same or very possibly worse.

Why action bias is hazardous

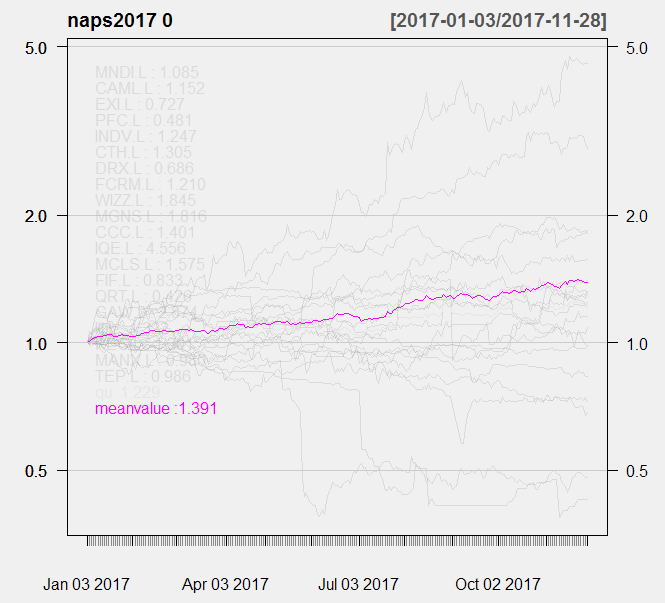

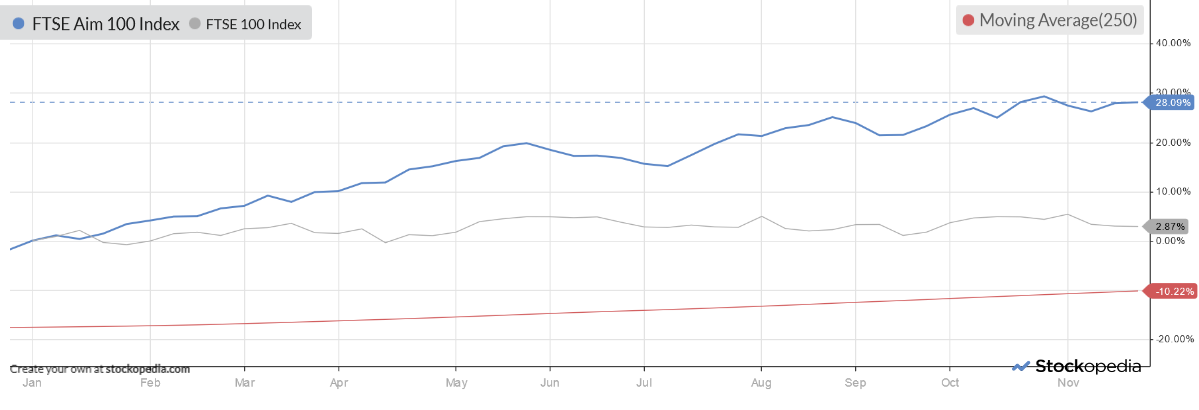

In practice, the immediate result of a bad dose of action bias is over-trading. The desire for a sense of control - whether it’s caused by boredom, overconfidence, chasing new ideas or even blind panic - leads to unnecessary trading. It’s the costs connected with all that trading that can damage returns.

Research back in 2000 by the behavioural finance professors Brad Barber and Terrance Odean, found that individual investors pay a “tremendous performance penalty” for active trading. Their analysis of accounts at a large American discount stock broker between 1991 to 1996, found that those trading the most earned an 11.4 percent annual return, while the market returned 17.9 percent.

They found that a massive part of the problem, was that the average portfolio saw a 75 percent annual turnover. And it was the spreads and commission fees on those trades that proved…