A few months after launching the Woodford Equity Income Fund in June 2014, Neil Woodford’s team published what’s known as its Active Share score. In doing so, they made a bold statement about the type of investor that Mr Woodford was...

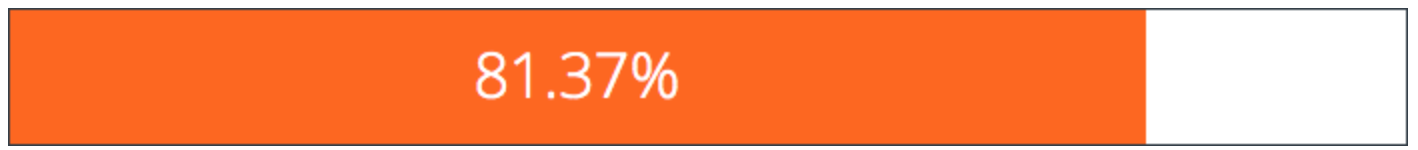

Active Share is a way of measuring how ‘active’ a fund manager is (when it comes to using skill and expertise) in constructing a portfolio. At the time, Mr Woodford was seen as one of Britain’s best money managers. And he was certainly by no means the only one to highlight his fund’s Active Share in the name of ‘transparency’. With a high Active Share score, he was effectively able to say: “look at how different my fund is to its benchmark”. And it really was. This was the score:

But the subsequent collapse of the Woodford Equity Income Fund shows why Active Share can be at best misleading, and at worst, utterly useless. In just over a decade since it was introduced, Active Share has gone from being an interesting comparison tool to a measurement hijacked by parts of the fund management industry and touted as proof of being special. In reality, it may well be nothing of the sort.

How Active Share sets fund managers apart

In active fund management, the standard test of success (or otherwise) of a fund is how it performs against a relevant benchmark index. Those managers that outperform their index get the glory (and big fund inflows), although their outperformance is statistically short-lived.

Meanwhile, those that underperform their index suffer the indignity that their investors could have done better by buying the index ‘tracker’ and saving the active management fees.

This issue of paying relatively high active management fees for poor performance is an extremely sensitive one for the fund management industry. There is just no getting away from the fact that reliable performance - let alone consistent outperformance - is very hard to find among professional money managers. So why would anyone pay the high fees, which themselves drag down returns?

To get an idea of the scale of the problem, just look at the performance of US managers last year. According to Morningstar, of all the 429 funds it rated as Bronze or better in 2018, 91 percent of them lost money in 2018. Only 38 made…