Readers who follow Burford Capital (LON:BUR) Burford will know that it has done very well out of two big cases: Petersen and Teinver. I've been trying to work out just how reliant Burford has been on these two interests.

Burford's aggregate income for the two calendar years 2017 and 2018 break down as:

Realised investment gains: $294m

Unrealised gains: $422m

Other income: $ 45m

The original costs of Petersen and Tenvier have been reported as $20m and $13m respectively.

Looking at the RNSs they started selling interests in these two cases from late 2016 (a very small interest in Petersen).

Up to July 2018 Burford had sold 28.75% of its interest in Petersen for $136m - so a realised gain of $130m (136-(20*28.75%)).

And it had sold all its interest in Tenvier for a realised gain of $94m (107-13).

Realised gains (calculated as proceeds less reported original cost) from these two cases in 2017 and 2018 would be a little short of $224m (as a v small stake was sold in late 2016).

In July 2018 Burford sold 3.75% of Petersen for $30m, reporting that priced its original investment at $800m - but after this sale its remaining entitlement was down to 71.25%. Valued at the price achieved in this sale that would be worth $570m, against an original cost of c$14m ($20m @71.25%) - equating to an unrealised gain of $556m.

However, the allocation of gains between realised and unrealised over a two year period can only be accurately done if one knows the fair value at the end of the first year. I don't.

But if Burford applied a fair value of $570m to Petersen at December 2018 it would suggest that the total of recognised and unrecognised gains over the two years to December 2018 of $780m (224+556) - against reported total realised and unrealised gains of $716m.

This suggests that Peterson had not been fully written up. But it does seem that the good figures reported over the last two years may have been largely reliant on just two cases.

shipoffrogs,

I think you're making things conceptually confusing by using the phrase 'unrealised gains' as opposed to the actual nomenclature used in Burford's statutory accounts: 'Fair value movement (net of transfers to realisations)'.

The distinction is important because the numbers you have used for your aggregate figure of $422m for 2017 and 2018 include negative values which arise from backing out previously recorded unrealised gains in order to avoid double counting of income (for anyone trying to follow this, see page 85 of Burford's 2018 Annual Report - the numbers concerned are 229,739 for 2018 and 191,830 for 2017).

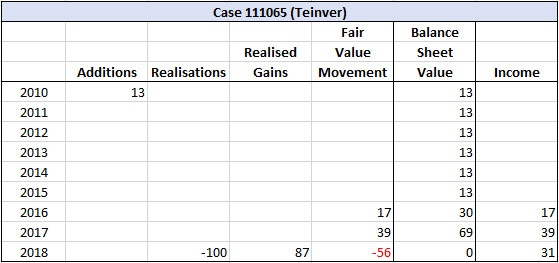

The Teinver case provides a good example of how these negative fair value movements arise from an accounting perspective. We have a full valuation history for Teinver because Burford provided it in their May 30 press release which announced the successful conclusion of the case:

Now that this investment has concluded, Burford is able to provide a valuation history for the matter, which illustrates Burford’s longstanding and conservative valuation process. At the end of 2016, at a point when the arbitral tribunal had decided the key question of jurisdiction in Teinver’s favour but had not decided the merits of the case, the investment was carried at a fair value of $30 million, $17 million of which was recognised as an unrealised gain (19% of the ultimate total profit) and $13 million of which was cost. During 2017, the arbitral tribunal decided the entire matter in Teinver’s favour and awarded it substantial damages, and Burford increased the investment’s fair value by $39 million to $69 million, generating $39 million of unrealised gain and bringing the total amount of unrealised gain to $56 million (60% of the ultimate profit). In 2018, when Burford sold the investment, it recognised a further $31 million of income to bring the matter to $100 million of proceeds and an $87 million realised gain. Now, in 2019, Burford will recognise the final $7 million of income associated with the put’s expiration.

The key point here is that when Burford achieved the cash realisation, the full realised gain was recorded in the accounts, not just the marginal gain on top of previously recorded unrealised gains. So, in 2018 an $87m realised gain was recognised in respect of Teinver even though unrealised gains of $17m and $39m had already been recorded in 2016 and 2017. Therefore, in order to ensure that the recognised income for the period was only $31m, a negative fair value movement was required to unwind the unrealised gains. If that doesn't make sense, then hopefully the table below explains it better:

As for Petersen, it's anyone's guess what the fair value movements were for that particular case during 2017 and 2018, but past statements from management suggest that the balance sheet valuation is conservative and below that implied by secondary market transactions. The first disposal took place in Dec 2016, with just 1% of Burford's interest sold for $4m, implying a $400m valuation for the original stake. This is what Burford said about the fair value assessment of the residual holding (apologies for the long quote, but it's an important one as it outlines management's philosophy at the time on fair values in relation to secondary market sales):

The development of secondary market activity naturally introduces the IFRS treatment of such transactions and their impact on our long-running discussion of fair value. It is inescapable that a significant secondary market transaction is a potentially key input into our determination of the fair value of an investment, and to the extent that there is truly a secondary market with appetite for a significant amount of one of our investments, we are to some extent joining the mainstream of the financial services world where market-based pricing is accepted unquestioningly as the basis for accounting “marks” on assets. We do, however, remain cautious, as we remain entirely aware that a litigation investment is capable of going to zero in one fell swoop, unlike many other categories of assets. Thus, we do not reflexively accept a market price for a portion of one of our investments as being necessarily indicative of the market clearing price for the investment or the appropriate carrying value for Burford’s accounts. Instead, we engage in more analysis, including looking at the size of the transaction and the market conditions around the offering, especially given the early days of this secondary market process. As a result, despite concluding a small toehold Petersen sale in December 2016 at what was ostensibly a $400 million implied valuation for our investment, for the reasons outlined above we did not believe that the sale of a mere 1% of the investment made it appropriate to value the entire investment at that implied value, and we did not do so; we increased the fair value of the Petersen investment to a level substantially less than that implied value in 2016, although it was our largest fair value adjustment.

[Source: Burford Annual Report 2016, pages 14/15]

This conservative approach to the valuation of Petersen appeared to be still operative in 2017, judging by management's discussion in the 2017 Annual Report (page 23):

In late 2016 and the first half of 2017, Burford sold 25% of its interest in the Petersen outcome into a secondary market we are working to build. The sale price of that interest was $106 million; Burford’s investment to date was approximately $17 million. Thus, Burford has no risk of principal loss in the matter and continues to hold 75% of its entitlement.

Since the secondary sales, there has been trading activity in the secondary market throughout the year at varying price levels, with the weighted average price in 2017 implying a value of around $660 million for Burford’s total original investment – in other words, the value placed on Petersen by third party investors has continued to climb from the $440 million valuation implied by our final tranche of sales.

We have thus increased the carrying value of our remaining investment in Petersen. We do not release individual investment carrying values for reasons of client confidentiality and litigation strategy but we can say that we have acted conservatively with respect to Petersen as is our general practice. In the end, we altered the carrying value of 15 investments in 2017 and the net increase in value across all of those investments was $181 million, so it is clear that we have not increased the carrying value of Petersen to anything approaching its secondary market trading level, which we do not regard as determinative of our own carrying value.

And from 2018's Interim Report (page 7):

In order to hold Burford’s cash exposure to the YPF claims relatively constant, we decided to finance our payment to Eton Park by selling some further interests in our Petersen entitlement, and contemporaneously with closing the Eton Park transaction, we sold 3.75% of our entitlement for an effective cash price of $30 million, implying a valuation of $800 million for our original total Petersen entitlement, although we carry our Petersen investment at a lower carrying value than that for the reasons we have enunciated previously.

Interestingly, there was no mention in 2019's recently released Interim Report of Petersen being held at a value below that implied by the 10% secondary market sale in late June for $100m, but unless Burford is privy to some information that is not in the public domain (e.g. an 'understanding' with Argentina that a settlement will be made after the election has been held in October) then I think it would be imprudent for BUR to hold Petersen at the $612.5m valuation implied by the June disposal, even though 11 institutional investors participated in the sale and it was heavily over-subscribed. A subsequent loss of the Petersen case would result in a huge write-off which I believe would completely torpedo Burford's claims to conservative investment valuation and be a major embarrassment for the company.

Whatever, I don't think there's any doubt that the Teinver and Petersen cases have been major drivers of Burford's glowing financial results over the past three years and I suspect there will always be some caution amongst investors regarding the company's valuation until it has been demonstrated that high investment returns can be maintained in the absence of these high profile outliers, or that cases with such asymmetric outcomes aren't as rare as might be currently believed. Additionally, Petersen in particular has given management the option to smooth profits (I hesitate to use the word 'manipulate'), and although I do have concerns about the balance sheet value of this case, I'm certainly very much in favour of de-risking the investment through secondary market sales.