If you had invested $1 in Berkshire Hathaway in 1976, that investment would have grown to more than $1500 by the end of 2011. That’s an extraordinary result. At the same time, this performance presents an interesting irony. Achieving these results is not rocket science. Buffett once said:

‘In investing it is not necessary to do extraordinary things to get extraordinary results’.

It’s a great line, but some people misread it. They attribute Buffett’s returns to luck. Warren made this point in The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville. He imagined a coin-flipping contest where 225 million people each flipped a coin once per day. After ten days, roughly 215 people would have gotten ten heads in a row — not because of skill, but simply due to luck.

Buffett then introduced a key point: if winners all used the same approach, their success might be due to a specific strategy, rather than just chance. Buffett noted that:

‘A disproportionate number of successful coin-flippers in the investment world came from a very small intellectual village that could be called Graham-and-Doddsville.’

Benjamin Graham and David Dodd were the founding fathers of value investing. They emphasised buying securities at a ‘cheap’ price (i.e. for less than their intrinsic value).

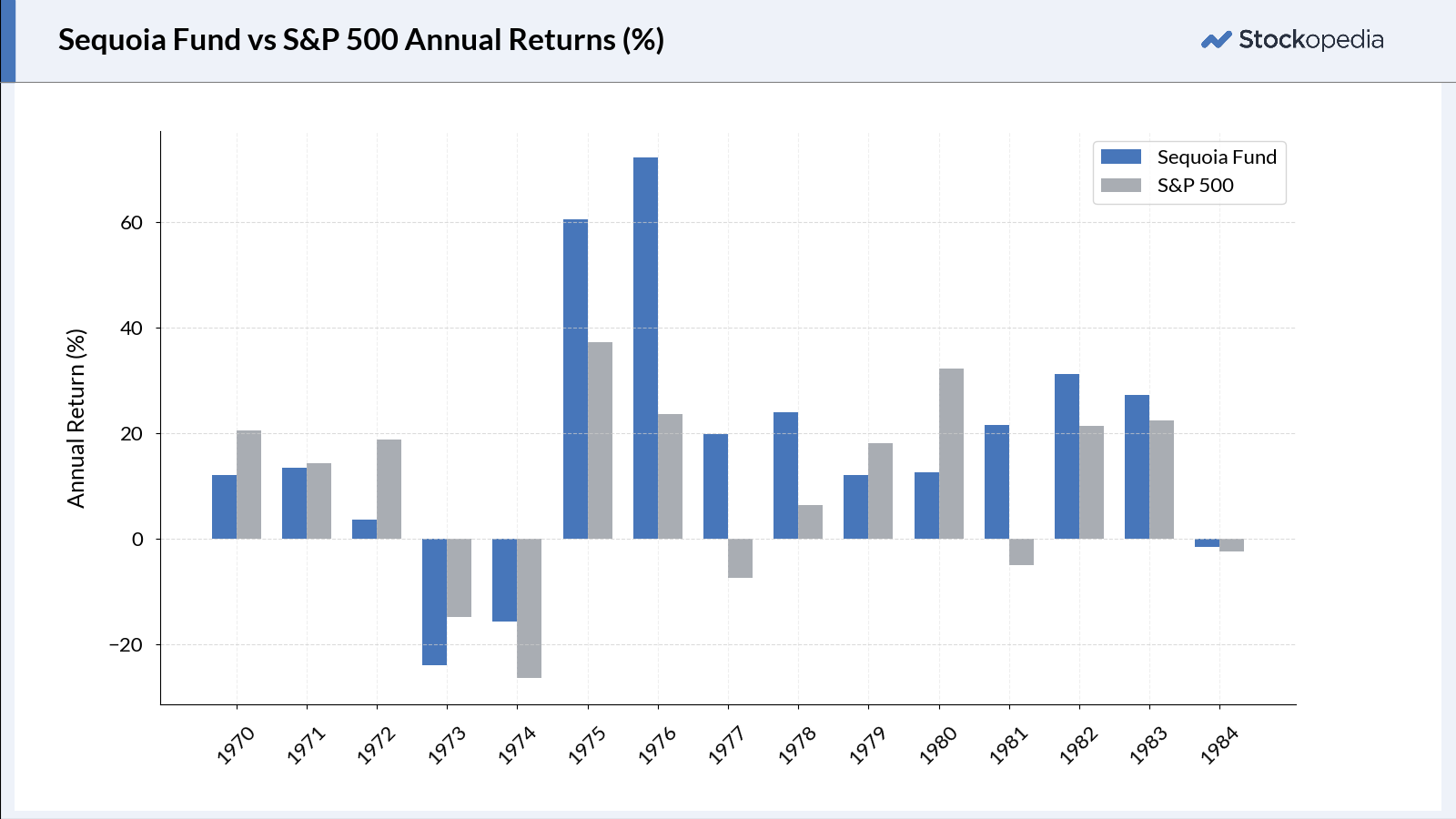

Buffett highlighted a selection of friends and acquaintances he considered true Graham-and-Doddsville-style investors. Each of them had outperformed the market over the long-run. For instance, the following chart shows the record of the Sequoia Fund, which was managed by Bill Ruane, whom Buffett met in 1951 in an investment class taught by Ben Graham.

Reverse engineering Buffett’s Alpha

At the same time, it’s easy to cherry-pick a few success stories, while overlooking other investors who followed the strategies of Graham and Dodd, but nevertheless failed. There must be a better way to explain Buffett's success…

In 2013, three quantitative researchers —Frazzini, Kabiller, and Pedersen— set out to understand Warren Buffett’s performance using a more data-driven approach. They applied regression analysis, a statistical method that examines how Buffett’s portfolio returns moved in relation to well-known factors such as quality, value, and momentum.

Their method was as follows: for each factor, they calculated a ‘factor premium’:

- For the value factor, the factor premium was the extent to which ‘cheap’ stocks (those with low price-to-book ratios) outperformed…