The recent surge in gold prices has brought a renewed interest in the sector from investors, and it is leading many to learn new terminology and concepts that don’t apply to non-mining sectors. There is a popular joke that a gold mine is a hole with a liar standing at the top. There is perhaps an uncomfortable truth to this, as it is impossible to know what is truly underground without digging it up. Faced with having the wool pulled over their eyes too many times, investors and banks now demand that mining companies provide independently compiled reports that model the underground gold-bearing structure [such as those compiled to the industry standard Australian "Joint Ore Reserves Committee" (JORC) Code].

Exploration activity usually starts by taking electromagnetic surveys, followed by soil samples or rock chips in areas that look similar to previous gold finds. Promising areas are followed up by drilling holes intended to intersect the mineralisation. The more holes that are drilled, and how tightly spaced they are, give greater confidence in the underlying gold-bearing structure. However, there is still uncertainty, and the independent reports reflect this by providing the amount of resources that may be present in different categories, of increasing confidence:

- Inferred: Lowest confidence. Only general geological information; significant uncertainty.

- Indicated: Moderate confidence. Quantity and grade are reasonably well understood.

- Measured: Highest confidence. Quantity, grade, and continuity are well established.

Then there is the issue of whether these resources can be profitably extracted. In order to finance a mine, investors demand a Feasibility Study, which models the economics. Resources that are considered economically extractable are known as reserves, and are reported in two categories:

- Probable: reasonable but lower confidence in extraction feasibility, or with economics, preliminary feasibility studies.

- Proven: highest confidence in extraction feasibility and have been economically evaluated.

Whether a mine gets built or not depends on what is known as a Final Investment Decision. Those putting up the money will consider if the possible financial reward generates an acceptable return compared to the risk they are taking and how that return stacks up against other opportunities.

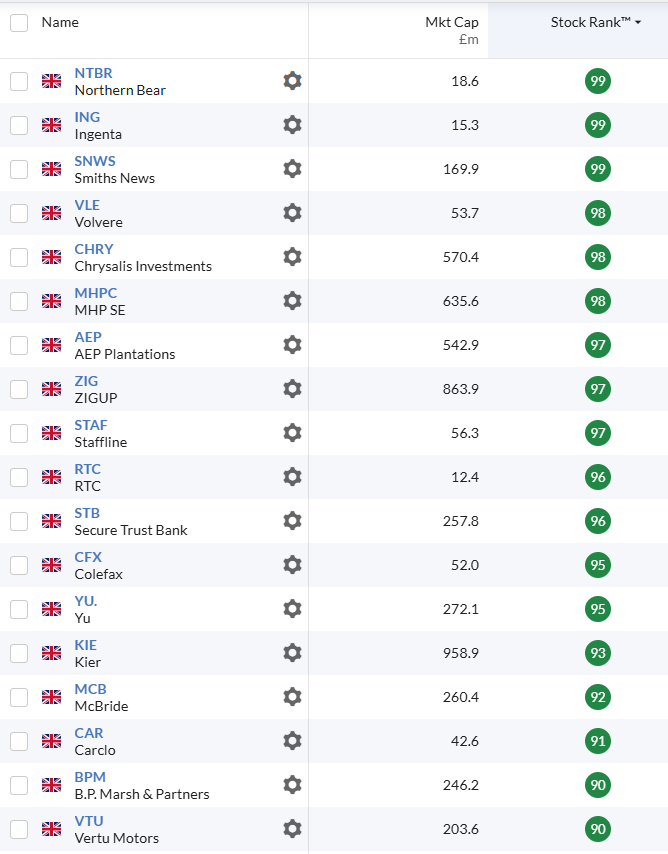

When considering this process, it struck me that this same probabilistic approach could be applied to Value Investing. Investing is a process wrought with uncertainty, where returns are based on an uncertain future. An investor's skill is in managing that uncertainty in order to profitably extract value. Value investors start with a general…