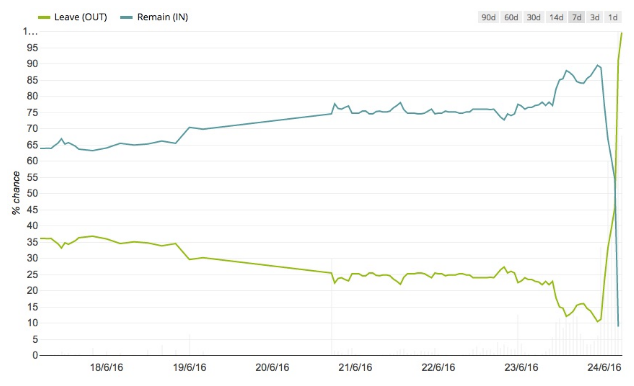

In the final stages of campaigning for the EU referendum, the outcome was clearly going to be close. One group with a particularly keen interest in the result were the pollsters and bookies who played a role in forecasting it. On past form, the pollsters had a lot to prove after failing to predict the 2015 general election. But they ended up getting it wrong again by mistakenly forecasting a slim victory for Remain.

For most of us, the signals from political polling and the betting markets don’t necessarily matter that much. But in the days ahead of the EU vote, the value of sterling leapt and many European markets saw gains. It suggested that traders believed what they were seeing in the forecasts. When that conviction turned out to be misplaced, those markets were hammered.

It’s an unusual case, but the forecasting errors in the referendum echo a wider problem with forecasting generally, especially in the stock market. Not only do analyst forecasts often turn out to be wrong, but there’s a worrying inclination among investors to rely on them anyway.

The problem with forecasts

In Robbie Burns’ book, Trade Like a Shark, he makes the following observation about the usefulness of broker notes: “If brokers really knew what they were talking about do you think they would (a) continue commuting into the office every day, or (b) take their laptop to Barbados and stay there? (P.S. it’s ‘b’).”

That view neatly sums up a lot of the work that has been done into the reliability of broker forecasts. Among the chief criticisms are that analysts are prone to being overconfident, which can lead to over-optimistic forecasts. In addition, the whole structure of the investment research industry has been questioned for compromising the independence of analysts. Arguably, some feel they need to be bullish in their forecasts in order to keep corporate brokerage clients happy, and ultimately keep their jobs.

In terms of analysts’ success rates, some of the most interesting studies have been done by David Dreman. He’s a well known contrarian asset manager whose strategies are based on stock market psychology.

Dreman studied a sample of more than 800,000 individual analysts’ estimates in the US market between 1973 and 1991 and found that the average error rate was 40% annually. Not only was that a terrible record, but those analysts were…