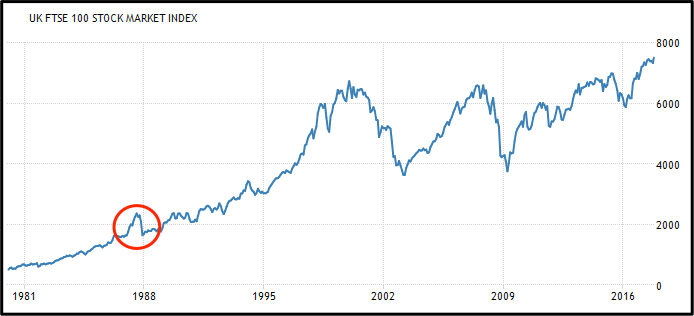

Thirty years ago this month Black Monday saw stock markets crash around the world. After several months of dramatic gains, the collapse unfolded on October 19, 1987, sweeping through Asia, Europe and the United States. By the end of that month, the FTSE 100 had fallen by just over 26 percent.

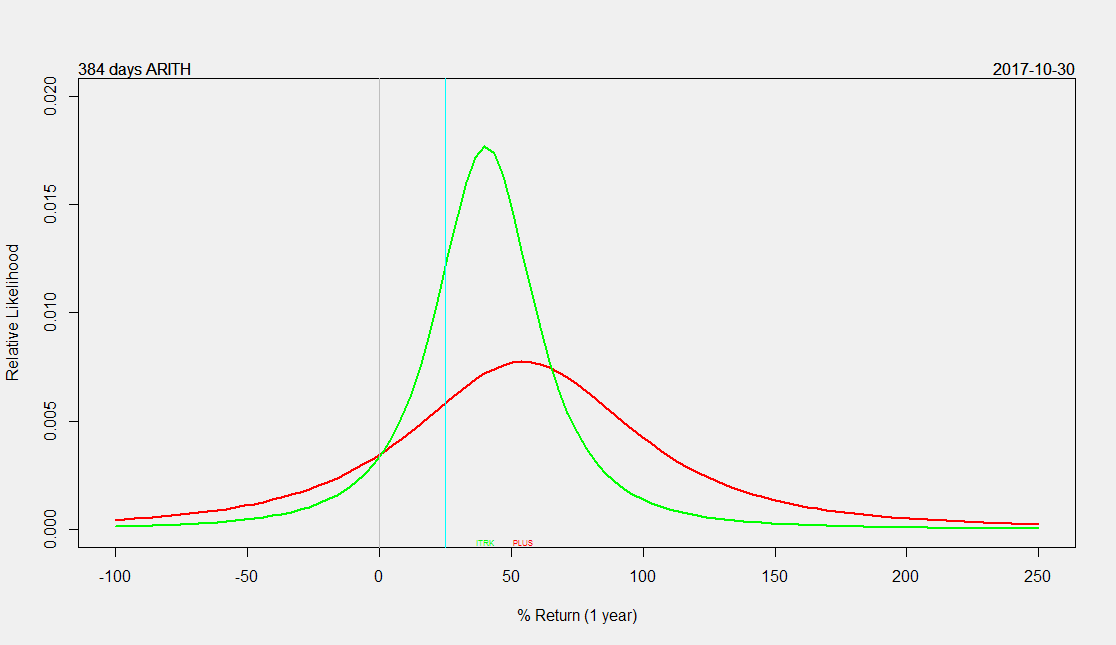

For some, the current market conditions are reminiscent - and perhaps a timely reminder - of how stomach-churning market turmoil can be. So it’s worth having a think about what action can be taken to prepare for periods of volatility, and even a crash.

Drivers of the ‘87 crash

While ‘87 was before my time (as far as watching markets goes), it’s clear that prices had been on a blistering run that year. It’s also certain that the crash caused a huge amount of justified fear. Over long enough periods, price charts will show events like these as mere bumps in the road - yet it was much more serious than that at the time.

Chart: Trading Economics

But what this chart does make clear is that the ‘87 crash wasn’t a prelude to a bear market. Rather than falling further, prices generally recovered within a couple of years.

As an aside, a major feature of the recovery was that the Bank of England cut interest rates (from 9.8 to 8.3 percent between August and December that year) to reinvigorate the market. The backdrop now is very different. Rates of sub- 0.5 percent since 2009 have been a massive boost to equities. But the Bank wouldn’t be able to help in the same way if the market crashed now - although few are predicting that will happen.

Stretched valuations cause concern

There’s nothing quite like a major anniversary as a chance to draw (sometimes spurious) comparisons. But thirty years on, there are at least a few echoes of ‘87 in the market right now.

For the most part it’s because valuations appear high - and stretched in places. The US market has been unstoppable for eight years, and we’ve seen strong gains in the UK too (although nowhere near as extreme as in ‘87). In parts, expectations are very high, which means that stocks - especially small caps - are being crushed for missing earnings forecasts. That’s exactly what we’ve seen recently in shares like Low & Bonar,…