It’s an axiom of standard economics that you don’t get above average returns without taking above average risks. No risk, no reward. It’s an appealing idea, an extension of the entrepreneur's creed: you don't become successful without taking chances. It’s a meme that’s gone viral, an idea that permeates discussions about investment, drives hard headed analysis and leads us to celebrate the risk taking achievers in society.

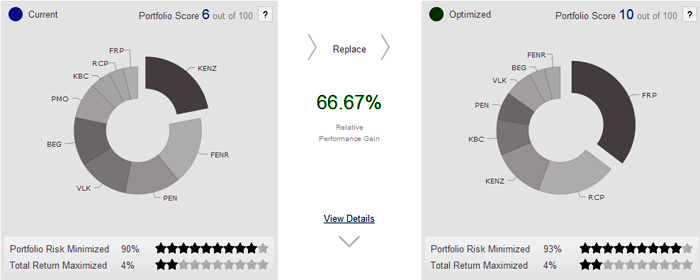

And of course it’s a bucketload of hogwash. In fact, lower risk portfolios will tend to outperform higher risk ones. High risk stocks are dangerous rubbish, and offer not excess returns but excess losses. They’re a one way ticket to the seedy side of the market.

The idea that you only get excess returns by taking excess risks is a prediction of the Capital Asset Pricing Model – the default model of asset pricing in traditional economics (see Alpha and Beta - Beware Gift-Bearing Greeks). CAPM is the overt expression of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, the idea that the right price for a security is the current price, because the markets will price in all known information about the security, and weight this against all other securities.

Mostly, serious economists no longer believe in the strong version of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis for the very good reason that markets consistently refuse to behave in even a vaguely efficient way. There are lots of arguments about how efficient markets actually are, but a rough summary is that they’re roughly efficient most of the time, and occasionally completely barking mad. Although “occasionally” is a moot term, given the frequent and violent violations of efficiency.

The idea that risk and reward are related springs from CAPM, because in the model risk is equated with volatility, the jitteriness of a stock’s price. A stock that rarely jumps about in price has low volatility and considered to be low risk. One that does the opposite is high risk. Volatility is measured by something called beta, which tells us how volatile a stock is compared to the rest of the market, and beta is often related to risk: higher beta stocks are higher risk.

We should treat that last statement with a certain amount of caution. If beta measures risk it does so only in the short term – after all, if a high tech stock goes…