What should I do if my stock gets a takeover offer?

Corporate actions are commonplace in financial markets. One function of being listed is that companies have a daily price at which the business is valued that is visible to all. If the market views the prospects significantly more negatively than a competitor or private equity fund, then these may swoop in and make an offer to own the whole business.

Conversely, all companies are listed so they can access capital markets, (or they wanted to access them in the past). This means that many companies will also turn acquirer if the right opportunity presents itself. Investors are likely to experience many takeovers in an investing lifetime, and knowing what is likely to happen and how to respond will be important for maximising returns.

When will I hear about a takeover?

Companies don't have to report every approach made to the board. A takeover can present a large distraction to a business, and boards will want to minimise the impact of this. Shareholders are likely to only hear about potential offers for one of the following reasons:

The offer is credible and is being seriously considered by the board. In making this decision, the board may have contacted major shareholders, taken them inside (revealing the information with the caveat that it limits them from trading the shares), and gauged their interest in accepting the offer.

The acquirer makes a statement to the market indicating their intention to make an offer. This is usually because the acquirer feels that their interest is credible, but the board disagrees. Many boards may do this because they believe in the long-term potential of the business. However, it isn't beyond the realm of possibility that the board may be more interested in preserving their own jobs, hence the desire of a potential acquirer to go straight to shareholders.

The possibility of a takeover is leaked to the press or has leaked to the market and caused a significant rise in the share price. In this case, regulatory authorities may contact a company, and if they confirm that an offer has been made, they will be forced to announce it. As you may expect, there are many reasons that the news may be leaked and from many parties. If investors trade on a rumour published in a reputable publication, this would not usually be considered inside information. However, shareholders should be careful when trading based on information shared from non-public sources. They may end up in hot water if it turns out they have been given material non-public information.

For companies subject to the Takeover Code (see below), a shareholder purchases shares which take them above the 30% holding level (or increases their holding if they already own more than 30% but less than 50%) and are forced to make a mandatory offer. A mandatory offer has to be in cash and at least made at the highest price paid for the shares in the previous twelve months. However, these events are relatively rare because this sort of offer often represents little premium and is, therefore, unlikely to be successful.

When news of an offer comes in, shareholders are likely to be pleased since the news invariably causes a rise in share price. However, concern over what to do next can cause a lot of uncertainty for shareholders. Before explaining ways to deal with this, it is worth understanding the different types of takeovers and what that might mean.

Types of takeover

An Offer or a Scheme of Arrangement

There are two types of takeovers that may be received in the UK: an Offer or a Scheme or Arrangement. With an offer, the acquirer only needs to reach 50% acceptance to take control of the company. However, it can still remain a listed entity with minority shareholders unless they receive 75% of the shares accepting the offer, at which point they can delist. Minority holders can remain in the unlisted equity. Many companies will keep their offer open, as they ultimately are interested in controlling the whole enterprise. Then, if the acquirer gets 90% acceptance, they can force the remaining holders to sell out at the same price. In reality, there are some aggressive actions that an acquirer can use to encourage the holdouts to capitulate. Delisting is common but may also be accompanied by rights issues or similar. Forced with the option of putting fresh capital into an unlisted stock with no guarantee of returns any time soon and no say in how the business is run, at this point, most holders simply take the cash. With an offer, shareholders that accept the offer then they will be restricted from trading their shares. However, they should receive consideration for the stake relatively quickly.

With a Scheme of Arrangement, the Scheme is approved by a court, at which point 100% of shares are owned by the acquirer. However, for the court to grant these schemes, 75% of the shares must have voted in favour. This gives certainty of control but requires a higher acceptance level to succeed. In this case, an investor's shares remain tradable until the Scheme is approved by the court and declared unconditional. Acquirers can choose to switch from a Scheme of Arrangement to an offer if they don't think they will get the votes but still want control of the business.

In both cases, the acquirer and acquiree will be required to hire financial advisers. At a minimum, the advisers have to confirm that the acquirer has the resources to complete the transaction. For the acquiree, the advisers will provide advice on whether the offer is in the best interests of shareholders or not.

The Takeover Code

Takeovers in the UK are regulated by the Takeover Panel. The Takeover Code, which they enforce, has a few aspects that investors will want to be aware of:

As already discussed, the Takeover Panel forces anyone who acquires more than 30% of the shares of a public company to make a mandatory offer for the rest of the shares at a level that at least equals the highest price they paid in the previous six months.

Once an approach has been made and announced to the market, The Takeover panel gives the acquirer a 28-day period to either announce a firm intention to make an offer or that it doesn't intend to make an offer. Colloquially, this is known as a "put-up-or-shut up." However, this period often gets extended at the target company's request, so it rarely represents a firm deadline.

If an acquirer chooses not to make an offer, then the Panel prevents them from returning within twelve months with another offer (unless someone else steps in with an interest.) A potential acquirer who already holds more than 50% of the shares may return with a more favourable offer, having only waited six months.

It is worth noting that companies listed but not domiciled in the UK are not subject to the Takeover Code. This may catch some investors out since they may see a shareholder in a foreign-domiciled company going above 30% and expect a mandatory offer which doesn't arrive.

Recommended or going hostile

Most acquirers will only proceed with a takeover if it is recommended to shareholders by the board of their target. The reason is that this makes the process far simpler. It is not unknown for shareholders to vote down an acquisition their board has recommended, but it is rare. The board usually has an inside track on the value of the business, and their advisers will help them to consider whether to recommend it or not. If the board say that an offer undervalues the company but the potential acquirer disagrees, they can appeal directly to shareholders with an offer. This is known as going "hostile". Understandably, this sort of situation is likely to be messier and more protracted than the average takeover process.

Cash or shares

The simplest type of takeover is when shareholders receive cash for their shares. This will be priced as a fixed cash amount per share. They may also receive a dividend either already declared or to be declared in the future, usually one that would have been paid by the company anyway. The only difference between this and the main cash payment is the timing and tax treatment.

In almost all cases, shareholders would rather receive cash, which they can redeploy how they see fit. However, for listed acquirers, there is the option to pay for an acquisition in shares or a mix of cash and stock. Sometimes, the larger shareholders want to retain exposure to any potential upside in the business performance, although diluted by being part of a larger group. Often, an all-share offer is because the offeror doesn't have the cash to pay outright, or its equity is much higher rated than the company they want to buy. These types of deals are often described in terms of the proportion of shares. For example, 0.1 shares of the acquirer for each share of the acquiree. It is this number that can be used to calculate the value of the offer. Using the same example, if the acquirer has a share price of £10, then the offer is being priced at £1. Of course, the companies involved will have a different number of shares in the issue, so it is also worth paying attention to the proportion of a company that will be owned of the enlarged group.

The pricing of an all-share deal is complicated by the shares in the acquirer being listed. When an all-share offer is made, the acquirer's shares often fall in response. This is partly because this opens up the possibility for merger arbitrage – where funds buy shares in the company being acquired and short shares in the acquirer. The idea is that the fund shorts the right number of shares so that when the deal completes, they can deliver the shares they receive from the takeover to close out their short. If they get their pricing right (and the deal is completed), they make a risk-free profit. In general, this is not a game that suits the individual investor. If a deal doesn't complete, the arbitrager can lose a lot of money. Hence, this is best for those who can diversify across many opportunities and are experienced at judging the chance of completion.

The other reason the share price of an acquirer may fall is known as The Winner's Curse. In a competitive auction, the winner is the one who is willing to overpay. So, the market may fear that the acquirer isn't getting the bargain they think they are. When the acquirer's share price falls, the offer becomes worth less. For this reason, all-share deals tend to be priced higher. However, it is certainly possible that an all-share deal becomes unattractive due to the share price move in response to the offer.

Pricing

There is a convention in the market that a takeover offer premium should be at least 30%. Any lower than this, then many boards will view that they would be better off remaining independent. Of course, acquirers want to pay the minimum they can get away with, so they may also gravitate around this figure. However, both sides will consider the recent trajectory of the share price. After all, they may have been negotiating for months before a takeover was made public. Most announcements will give not just the premium versus the last price before the offer is made public but also against the volume-weight average price (VWAP) of the previous three or six-month period. An acquirer is trying to convince shareholders that they are getting a good deal, so they will often pick the data that puts their offer in the best light.

There are several factors beyond recent share price direction that can influence how large a premium will be paid:

Type of acquirer

Analysing recent recommended takeovers reveals a difference in the average premium paid depending on whether the offer came from an industry rival or a private equity fund. Industry acquirers offered around 60%, whereas private equity offered around 40%, on average. It makes sense that industry buyers will pay more. They should be able to access synergies that other buyers can't. They also should better understand the underlying value of what they are buying. In contrast, a private equity buyer has fewer levers they can pull to enhance the business's underlying profitability, which is reflected in how much they are usually willing to offer. Note, however, that both these averages are above the 30% minimum market norm, so the premiums paid can vary over time

Shareholder structure

Having a large shareholder can be both a blessing and a curse regarding takeovers. If one shareholder owns more than 25% of the shares, they can block a takeover via a scheme of arrangement. A shareholder, or concert party that owns more than 50% can block any type of offer. In reality, any large stake probably acts as a blocker to corporate action. This is especially true for smaller companies where individual investors may not always vote their shares. This means that an acquirer needs to make an offer sufficiently attractive to this large shareholder. When we see takeovers with large premiums, say 100%+, this is usually due to the presence of a controlling shareholder who knows what the company is worth. However, a company takeover with a controlling shareholder is rarer because the acquirer still needs to believe they are getting a bargain.

Number of bidders

As anyone with experience in an auction knows, the best price is achieved when more than one serious bidder is interested in the asset. The presence of a known bidder, such as a private equity fund, will cause others in the industry to run their slide rule over the business.

There's no definitive way of working out if more bidders will arrive. However, several aspects may give clues, such as:

The presence of previous deals in the industry where one or more players were unsuccessful. This means that acquisitive and presumably well-funded competitors are in the sector.

The presence of more than one competitor on the shareholder register. It is unusual for competitors to invest in a business purely as an investment. Their stakes are usually intended to be strategic investments.

Stake-building by known acquirers. Once an offer is made public, the bidder may still acquire shares in the market to strengthen their hand. However, if they purchase shares above the level of their offer, the takeover code requires them to up it to at least that level. For this reason, they will not usually purchase stock above the current offer level. So, if another possible acquirer who has not yet bid is adding to their stake above the offer price, that is a sign that they may be preparing to swoop in.

When multiple bidders compete, they may outbid each other several times. However, the Takeover Panel will try to keep the process orderly and will usually set deadlines for bidders to raise their offers or withdraw from the race. This means the bidding war will not disrupt the business for too long.

Decision-making frameworks

When an offer is made, the options for investors are usually fairly simple: accept the offer via their broker (or, for a Scheme of Arrangement, wait for this to be approved) or sell in the market when a takeover is announced. The benefit of selling immediately is that an investor makes a gain immediately, even if the takeover fails. However, other shareholders may do this, and investors are unlikely to get the full offer price. They also miss out on further gains if there is a competing bidder or an enhanced offer. The variety of possible outcomes makes deciding what to do in response to a takeover offer difficult, and no investor always gets it right. While most recommended takeovers complete, even if a firm offer has been made and recommended by the board, this is not guaranteed. The reason is that bidders often set pre-conditions that may need to be met.

Pre-conditions

Many companies understandably won't open up their books to a competitor until a firm offer is in place. The acquirer will then begin a process of due diligence. The Takeover Panel will not allow a company to pull out for minor reasons. However, if there are large undisclosed liabilities or accounting problems, these may well be considered material adverse developments and scupper the deal. It is not uncommon for acquirers to miss major problems in due diligence, have buyer's remorse, and then try to win their money back via the courts. However, investors shouldn't bank on this, and if there is any doubt over these factors, they should assume that the due diligence may fail.

The other major obstacle to takeovers completing is regulatory approval. Any corporate action in a regulated industry is likely to require approval from that regulator. In some UK industries, an acquisition by a foreign company may require government approval, sometimes up to the Secretary of State. In some jurisdictions, and especially when natural resources are involved, governments or other companies may have pre-emption rights that allow them to acquire the assets instead of the acquirer. This can make such deals very complicated. All these are not usually unsurmountable obstacles to a deal completing. However, these factors can extend the timeline for completing a deal.

Deal timeline

Any firm offer will be accompanied by a deal timeline, which tells shareholders when they can expect events to occur and, most importantly, when they should receive their cash or new shares. Where pre-conditions exist, this timeline may get extended. Most deals have what is known as a long-stop date, at which point the deal lapses. Despite the name, these dates can be extended with agreement from both parties. However, they exist to protect shareholders from a takeover dragging on so long that the deal is no longer worthwhile.

Thinking probabilistically

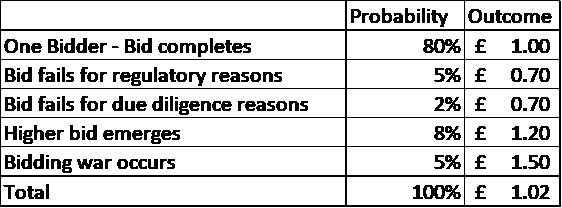

With so many possible outcomes, one of the best ways to make a decision is to list all the possible outcomes and estimate the return to shareholders and the probability of each outcome. Multiplying the estimated value of each outcome and the probability of it happening and then adding these up gives an expected value. It will look something like this:

Of course, it takes some judgment to assign probabilities and outcome values, but the result will be an investor's best guess of the expected value of the current situation. If there is no firm bid, but one is being considered, the number of outcomes may well be wider, but the same principles can be applied. An investor can then compare the expected value of this outcome with the current share price and other investment opportunities to decide whether to sell in the market or not. A more advanced method would be to estimate the time for a deal to complete and adjust for the time value of money, but this may not be necessary for a deal expected to happen quickly.

Minimising regret

If the probabilistic approach seems a bit too complicated, one useful mental model for making decisions about complex matters can be applying the lowest regret principle. In this case, an investor imagines how much regret they would feel if they sold their shares, and a higher bid emerges. They compare this to the imagined regret if they hold on and the bid fails. They then follow the action that leads to the least regret. This thought process helps elicit how an investor truly feels about the situation and can help make decisions when possible outcomes are too broad to analyse thoroughly. When it comes to decisions around takeovers, it is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.