What aerospace engineers can teach investors about selling strategy

First Officer: “Captain - one of our engines is failing.”

Captain: “Set throttle to maximum thrust on the failing engine.”

Even if you have never watched a sci-fi movie before, our captain’s response may sound a little odd to you, and for good reason. Engineering systems are designed to reallocate resources away from failing components and towards working components to ensure the system continues to work. Upon engine failure during flight, a pilot will redirect fuel away from the broken engine towards a working one, instead of doubling down efforts to the broken engine. This is synonymous to reducing capital from a losing stock market position and redirecting it to a working one.

“Run your winners and sell your losers” - Timeless advice endorsed by many successful investors including the Paul Tudor-Jones, ‘Naked Trader’ Robbie Burns and Mark Minervini and advice that you have probably heard hundreds of times before. And yet evidence shows many of us succumb to doing the very opposite. We persistently hold onto our losers as they continue to fall, vowing to sell them only once they return to their previous high. There is also a temptation to ‘average down’ in these stocks, which involves buying more of the losing stock, usually funded by selling our recent winners.

In ‘The Art of Execution’, one of the best books on selling strategy, Lee Freeman-Shor analyses the strategies adopted by 45 of the world’s top investors, summarising them into winning and losing styles. One of winning styles is an ‘Assassin’-like approach to losses - cutting them quickly, and a ‘Connoisseur’ approach to winners - being patient and allowing gains to compound over time.

Bill O’Neil had advocated a similar style several years before in his book ‘How to Make Money in Stocks’. Bill took this approach further, preferring to pyramid up position sizes. He suggested selling losers quickly and averaging up, buying more of a stock after it has risen in price.

Why selling strategies matter

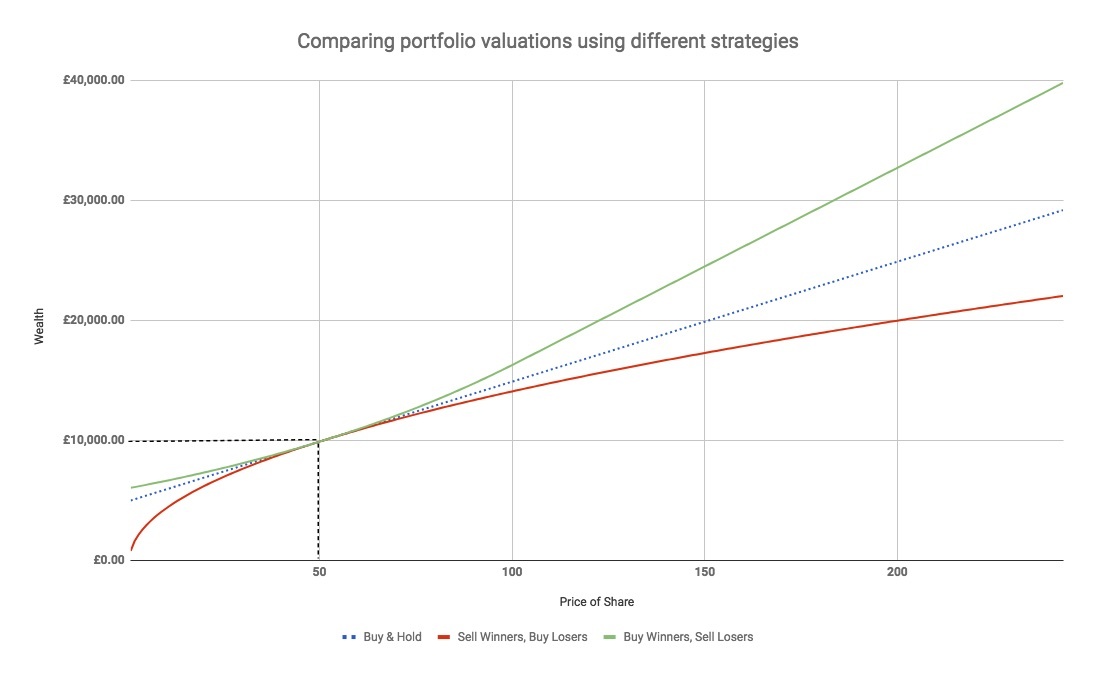

To outline the differences that these various strategies can have on your wealth, assume you have a portfolio which only holds two positions: an investment in Stock A and a Cash position. The starting value of the portfolio is £10,000 and it holds equal weight in Stock and Cash - 100 shares of Stock A at £50 per share and a £5000 cash position. For simplicity we assume cash has a constant return of 0%.

We then compare how the valuation of the portfolio changes for each of the strategies given a change in the price of Stock A.

Our ‘Buy and Hold’ investor does nothing in reaction to the price of Stock A - the ‘Rabbit’ as eluded by Lee Freeman-Shor.

Our “Sell Winners, Buy Losers” keeps topping up his losing position from the (relatively winning) cash allocation, ensuring that the portfolio keeps its initial equal weighted allocation.

Our “Buy Winners, Sell Losers” investor increases her allocation to Stock A funded from the cash position (the relative loser) as the price of Stock A rises, maxing out to 100% of the portfolio. As the price of Stock A falls she decreases her position, increasing her allocation to the relatively winning cash position.

The chart provides a visual representation of some of the troubles of selling winners to buy losers. Not only does this strategy start to truncate your upside as the price rises, it also exposes you to increasing losses as the price of Stock A falls. Reducing losers and topping up winners may be behaviourally difficult, but it both reduces your downside and increases your upside at an increasing rate as the stock rises in price.

“But wait,” I hear you say, “… Stock A might bounce back”.

Well this is certainly true. Lee Freeman-Shor also described another winning strategy of the “Hunter”, the expert analyst type who doubled down in losing shares and claimed a profit as they rebounded. Our very own Paul Scott claimed a big win when he invested in BooHoo soon after a profit warning and rode it up during its subsequent recovery.

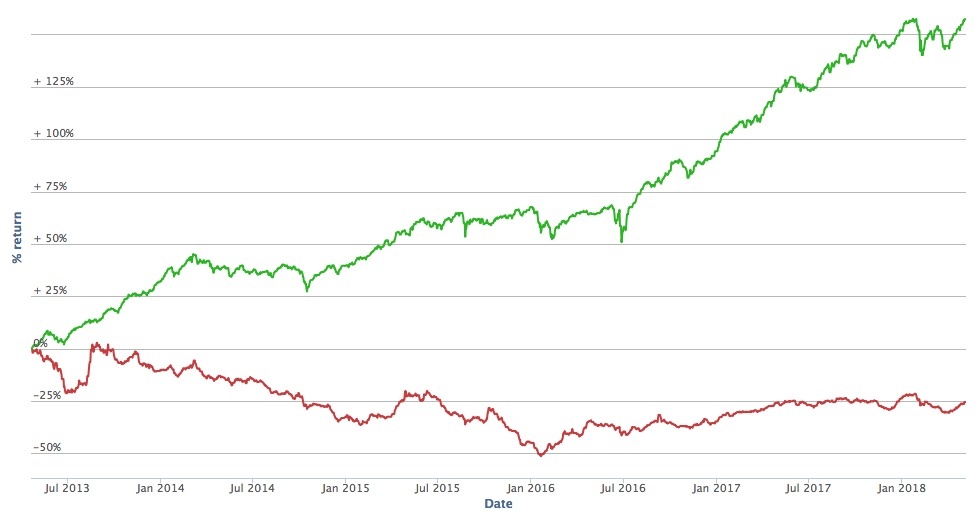

But the question is, do you want to bet against the base rates? Lee Freeman-Shor found two-thirds of cut losing investments didn’t return to their purchase prices. Meanwhile, Stockopedia’s excellent Profit Warning Survival Guide showed that after a year had passed, only 13.2% of stocks ended with their share price back above the price before the warning. Finally, when you compare how high MomentumRank stocks (green) and low MomentumRank stocks (red) have performed over time, you can see the trend would not be your friend.

Now I am not suggesting that you should instantly sell all your holdings and move them all into your biggest winner - it’s important to be prudent with regards to risk management and position sizing. However, which business units to allocate capital to is a key part of any business. A study by strategy consultants McKinsey states:

“Companies that reallocated more resources—the top third of our sample, shifting an average of 56 percent of capital across business units over the entire 15-year period—earned, on average, 30 percent higher total returns to shareholders annually than companies in the bottom third of the sample. This result was surprisingly consistent across all sectors of the economy. It seems that when companies disproportionately invest in value-creating businesses, they generate a mutually reinforcing cycle of growth”

If good capital management - not chasing good money into bad projects - can add substantial shareholder value to billion dollar businesses, imagine the impact the same approach could have on your portfolio.

If you want to know more about Stockopedia’s Profit Warning research, click here, or check out this video of Ed Croft talking about the research at the recent Mello 2018 investment conference.

About Oliver Cooper

Disclaimer - This is not financial advice. Our content is intended to be used and must be used for information and education purposes only. Please read our disclaimer and terms and conditions to understand our obligations.

Thank you for taking the time to comment.

I agree that an entry point in a stock cannot have an impact on the price (unless you have a whale-like order size!) I think you are correct that the method of cutting losses incorporates the momentum effect but I believe that it also ingrains a discipline of good risk management.

With regards to ‘sell what you wouldn’t buy’ - I am interested in hearing more about how you adopt this, as I would think it would encourage the opposite effect of selling winners and holding losers. As an example, suppose that you follow a disciplined value process that only enters a position if the stock is priced less than X (where X is calculated using whatever valuation method you choose). If the price rise to 1.05 X, you therefore would sell as you wouldn’t buy at this price. On the contrary, it is fall to 0.95X, then it still meets your buy criteria, so continue to hold. It also meets the criteria at 0.9X, 0.8X etc…

This is of course synonymous to cutting winners short and holding losers. So what addition sell criteria do you employ whilst using this strategy to avoid falling into this trap?

In theory you need to have a bit of hysteresis (a no-action bias for borderline cases) so as to avoid flip-flop trading. In practice it tends to come naturally, because the universe of "stocks you wouldn't buy" is typically smaller than the universe of stocks you don't own.

Applied to familiar stock ranks, say you consider rank >80 as investable. You then drop stocks that go below that and replace them with the best ranked stock you don't have, which for typical portfolio sizes (well below 20% of the stock universe size) will be in the high 90s, so you get a natural buffer before your new entrant becomes uninvestable. Most investment strategies can be expressed as a ranking process.

You don't necessarily cut (price) winners or hold losers, unless your ranking is itself based (exclusively) on price movements.

Words are cheap. Anyone can say "Run winners and sell losers."

We all know that investing in shares is NOT A PRECISE SCIENCE.

The question is how to manage a portfolio and decide what to buy and sell and what reasoning will be used to underpin those transaction decisions.

The investor needs a disciplined approach based on a framework they have developed.

I use a system base on investigating the compound gain (Capital and dividend) of a share (Spreadsheet intensive) to help me make decisions.

I HAVE NEVER EVER SEEN ANY INVESTMENT ARTICLE DESCRIBING THE DETAILED DECISION MAKING METHODOLOGY USED BY AN INDIVIDUAL AND/OR ORGANISATION TO MAKE BUY OR SELL DECISIONS.

This tells me that most financial journalists are just clueless hacks.

I HAVE NEVER EVER

when the facts change, I change. If the company fundamentals are deteriorating you should sell independently of where the price is. If the story keeps getting better you hold on to it, well unless the company has run to its potentials. To let stock prices tell you what you should do is a very dangerous proposition. I suggest re-reading one of the classics of portfolio management like One Up on Wall street where Peter Lynch is clear about this. You can't knock the all mighty Peter.

There may be some sense here, but general rules have limited use. Take this example - no doubt luck at least as much as judgement. I bought IQE somewehere in the 20s with talk of a 35p target price. It drifted lower and lower, and I bought two more blocks of shares, finishing up with an average cost under 20p. Sold most of them at around 150p (I wasn't convinced the company was worth that) and the rest recently at over 100p. Obviously this doesn't happen every time, but simple averages fail to capture the fact that the possible upside is larger (although much less frequent) than the possible downside, which is limited to 100%. In fact, most shares lose money, the returns come from the minority that do very well and the dividends. Given that company results appear to be inherently unpredictable, it's hard to see how any rule can capture an effective strategy. On top of that, any generally successful strategy would necessarily be self defeating since investors as a whole cannot do better than the total market.

I have recently adopted this strategy and find that it is already showing some benefit.

Interesting comments. My view, for what it is worth, is that the average person is psychologically wired to invest in such a manner that they almost guarantee that they will lose. It requires discipline, patience and simplicity in order to be a successful investor.

Many people who invest do not do sufficient research, never mind having a buying strategy, too many do not have a selling strategy, and way too many investors panic and sell after a sudden fall in price, which may or may not be a cause to sell, but if you have no strategy then you are asking for trouble.

I agree strongly with the comment made by cig, in that you should sell what you would not buy, with the proviso that this will again only work if proper research is carried out, which of course cig infers.

Two of my own most successful investments in the last 12 months have been OXB and SXX which also require a degree of confidence in the management in those companies to actually deliver on the projects that they are planning to deliver upon.

I still believe that each of those companies has a significant upside over the next 5 to 10 years, and if I am correct then I will have made a very significant profit.

The challenge in such circumstances is whether to top-slice at any given time, as it is always difficult to predict when the market will react to such companies and rerate them, so I tend to buy and hold.

I find it interesting to read the views of others, and particularly like the way Robbie Burms explains his thinking.

It is trivially true that you will do best as an investor if you make sure only to back winners.

I am finding this thread interesting and would like to add a real life buying and selling example to it. Sprue Aegis SPRP joined AIM in May 2014 raising more money at £2 a share but it had been a good performer on OFEX or whatever it is now called for some time before that with some shareholders buying at just a few pence. The good results and performance continued and the shares peaked at over 350p in March 2015. Then forecasts were not met, but not to worry said the management it’s a fixable problem and by December 2015 the stock was almost back to it’s all time high. However into 2016 new troubles emerged, reassuring words from the management this is the last profit warning, we will get over it, trust us we will maintain the dividend.

By spring of this year new troubles arrived the cash pile now largely disappeared the dividend was then suspended and the share price now down below £1. At one time doe’s everyone’s sell signals kick in over this? Bear in mind some investors are STILL showing a multibagger at the current share price while others if still holding may be doing so since £3+ Harry hindsight always makes a profit but in the real world when would you have sold?

*Past performance is no indicator of future performance. Performance returns are based on hypothetical scenarios and do not represent an actual investment.

This site cannot substitute for professional investment advice or independent factual verification. To use Stockopedia, you must accept our Terms of Use, Privacy and Disclaimer & FSG. All services are provided by Stockopedia Ltd, United Kingdom (company number 06367267). For Australian users: Stockopedia Ltd, ABN 39 757 874 670 is a Corporate Authorised Representative of Daylight Financial Group Pty Ltd ABN 77 633 984 773, AFSL 521404.

The "failing engine" metaphor is intellectually dishonest: a failing engine is normally a pretty clear fact. The price of a stock going down is also a fact, but it does not give clear information about the health of the company unfortunately. Sometimes it's a dud, sometimes it's a bargain.

Anchoring on personal entry points ("sell your losers" etc) is just a symptom of a psychological bias (plain common sense should be enough to prove the entry point of an individual investor cannot under normal circumstances have an impact on the future prospects of a stock, and therefore on the investor's future performance) which just happens to "work" because it's a rough, deeply innumerate spin on momentum. If you like momentum please use the full price series data set, not a small noisy sample with just your last few trades (that's why Stocko uses the full data set to calculate momentum ranks rather than just Ed's trades).

The only rational "selling strategy" is "sell what you wouldn't buy". Everything else is a waste of brain cycles.